Something went Wrong

Try entering your email again or contact us at support@qfi.org

Try entering your email again or contact us at support@qfi.org

You’ll receive an email with a confirmation link soon.

Oct 23, 2023

By Fhiona Mackay, Director of Scotland’s National Centre for Languages

Recently, I have been contemplating my own language journey. I grew up in a Scots and English speaking home but considered myself monolingual. However, even before I started school, I was already a skilled language user. I could slip in and out of Scots and English without thinking that I was using two languages. I knew unconsciously that the way I spoke to my family was not the same ‘register’ that I used with my parents’ friends. I understood that Italian and Polish friends and family had different words and accents than the ones we used at home. I was not monolingual at all. How powerful would it have been if I, like my peers, was recognized as an emerging pluri-lingual person; already a skilled linguist with the potential to expand my existing repertoire of language(s) in useful and exciting ways?

Instead of considering our children and young people’s language learning experience as ‘filling an empty vessel’ full of new words and concepts, would a better starting point be to help our learners recognize the skills and abilities they already have? Being monolingual is not the norm; the human mind is not developed that way. Should we, therefore, encourage our learners to see that they are already developing the potential to communicate with a wide range of people, using a diverse range of skills, words, grammatical forms, dialetics, registers, etc? Perhaps this might be a way of dismissing the self-doubt that ‘languages are too hard.’ Could this counter the frustration about not being able to communicate effectively, or dispel the myth that somehow English speakers are genetically disposed not to learn other languages? If children and young people are supported to reflect on their language awareness and encouraged to explore the linguistic diversity that they use and encounter every day, then surely this is a better starting point for them to learn more.

Language skills are not reserved for the elite. I’ve heard some of the most skillful, creative examples of trans-languaging on a late night, inter-city train. Language in all its diversity is the birthright of everyone, and yet languages that are brought into the classroom are often seen as a barrier to learning. Let’s turn that around. Let’s recognize all language skills as beneficial, to be applauded and celebrated. By valuing the language we build self-esteem; we value the culture, the community and most importantly, the person. With no implicit hierarchy of languages, no language is more “useful” or “important” or “relevant” than another.

This year, one hundred teachers registered to take part in SCILT’s online Ukrainian classes. A year ago, they would never have foreseen the need to acquire a basic competency in Ukrainian. However, there they were, from all disciplines, understanding that even a little language can underpin a trauma-informed approach to education, and can make the world seem less scary and more welcoming to families whose lives have been turned upside down.

The ability to communicate across linguistic and cultural borders is a life-skill, not solely an academic pursuit. Language skills are not only valuable if fluency is achieved. I recently discovered this to my relief when my taxi to the airport in Salzburg was pulled over by the police and I was left in the middle of nowhere with a plane to catch. Language skills are life skills. Even basic language competency makes navigating the 21st century much easier. How could that be anything but an asset to the individual and to humanity?

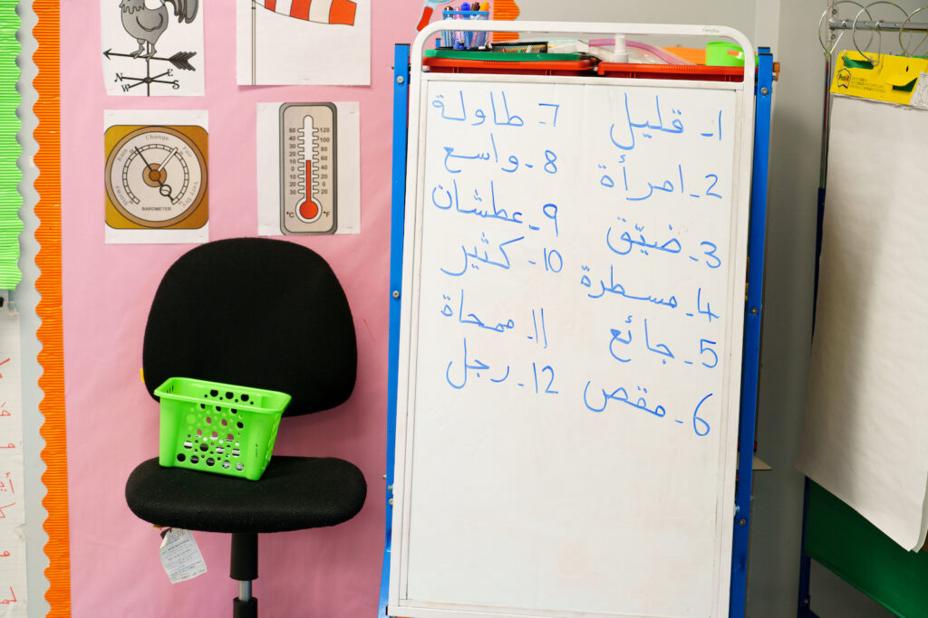

Working with SCILT affords me the opportunity to advocate for the benefits of multilingual societies across the entire Scottish nation and beyond. Our work with learners, teachers, families and community stakeholders is driven by the belief that a muti-lingual approach is socially just, and places high value on the skills that pluri-lingual people bring with them to their learning experience. Our approach to the learning and teaching of Arabic embodies these ideals. Importantly, our learning and teaching approaches offer a positive view of modern Arab life as well as drawing on rich historical heritage, thereby promoting inclusion and valuing diversity. Our program encourages learners to embrace the Arab world: it demystifies Arabic language and cultures as experienced here in our local communities and across the world; it encourages them to make links between Arabic and other languages they know and use. In other words, it enables Scotland’s children and young people to develop linguistic and communicative skills in the world’s fifth most spoken language and encourages them to recognise the commonalities in language, culture, and identity that link us all as citizens of the world.

The languages we use are at our very core. They are our mechanism for communicating who we are to those around us. They record our past, describe our pressent, and express our aspirations for the future. The most important thing we can do for learners is to create safe spaces for them to understand and develop their own linguistic identity, and appreciate how that allows them to relate to the world around them. I am so proud that SCILT can support educators to deliver a language-rich, culturally diverse education that every 21st century learner deserves.

Fhiona Mackay is the director of Scotland’s National Centre for Languages (SCILT) and the Confucius Institute for Scotland’s Schools (CISS) at the University of Strathclyde where she is a Principal Teaching Fellow. Joining SCILT in 2012 from her previous role at Education Scotland, Fhiona works with a wide range of national agencies and international partners to promote and support language learning across Scotland in schools and communities.

Fhiona recognises the importance of collaboration and the sharing of ideas, strategies, and research as a way of empowering members of the language community. In this way, she believes, we can ensure that languages are seen as key skills for life in a locally interdependent world and contribute to the development of a more inclusive and tolerant society.

Leading the SCILT/CISS, Fhiona sets the strategic direction of the organisation in full collaboration with the team. A passionate advocate for languages, , wherever they are spoken, used and learned across Scotland and beyond, she is equally avowed of the importance of high-quality professional learning and knowledge exchange for the teaching profession as key to continuously improving the learning experience of children and young people.