Something went Wrong

Try entering your email again or contact us at support@qfi.org

Try entering your email again or contact us at support@qfi.org

You’ll receive an email with a confirmation link soon.

Dec 11, 2025

By Veronica Merlo

For Arabic learners, these moments repeatedly manifest when uncovering the deep relationships between words that share a common root, recognizing the layers of meaning that connect them.

This can happen right from the very beginning, when acquiring basic vocabulary such as kitāb (book), discovering that together with yaktub (to write), kātib (writer), and maktaba (library, literally “the place of books”) all stem from the same root, k–t–b. The same root also opens the door to approach deeper concepts, such as realizing that maktūb (destiny), literally meaning “what is written”, is related to k–t–b, inviting reflection on the word’s underlying meaning from new perspectives.

Understanding these chains of relationships is not only intellectually rewarding; it also has the power to transform the vocabulary learning process and the broader language-learning path into an inspiring, meaningful and sustained experience, where structure and meaning constantly intertwine and endlessly unfold.

Inspired by an assignment on the role of theoretical linguistics in language instruction for the course Principles of Applied Linguistics, taught by Dr. Reem Bassiouney in the TAFL Master’s program at AUC, this blog post explores how Arabic morphological awareness, combined with semantic reflection, can enhance vocabulary acquisition, while nurturing learners’ curiosity, motivation and growth throughout their language learning journey.

Why morphology matters in learning vocabulary

Morphology, that is “the study of the internal structure of words and of the rules by which words are formed” (Fromkin et al., 2003, p. 76), enables learners to decode how words are built and interconnected through their smallest meaningful units, or morphemes. As Fromkin et al. (2003) affirm, understanding morphology is fundamental to truly knowing a language.

Remarkably, developing morphological awareness becomes a powerful tool in the context of vocabulary learning. As Nation (2013, as cited in Bakker, 2020) explains, knowing a word involves the understanding of its form, meaning, and use; here, multiple linguistic fields such as morphology, phonology, semantics, syntax and pragmatics intertwine. In this multidimensional process, recognizing the underlying structure of words lays the foundations for learners to make sense of how language functions as an interconnected system rather than a list of isolated terms.

Several studies have investigated the role of morphological instruction in vocabulary acquisition. For example, Pressley et al. (2007) examined how encouraging learners to engage in problem-solving by analyzing internal cues within words enhances vocabulary development (as cited in Bowers & Kirby, 2010).

In this sense, form-focused instruction that invites learners to actively explore, deconstruct and reconstruct words proves more effective than rote memorization, turning vocabulary learning into a creative and cognitively engaging process. As Laufer (2010) highlights: “doing something with a word is more effective than simply coming across it a number of times” (as cited in Bakker, 2020, p. 191).

Arabic morphology: roots and patterns to form meaning

Understanding morphology becomes even more essential in Arabic vocabulary acquisition because of the language’s specific morphological system. Unlike many Indo-European languages, Arabic features a non-concatenative morphology, in which words are formed from triliteral roots interwoven with specific patterns that modify meaning and grammatical function (Elkheir Elgobshawi, 2024).

This root-and-pattern system allows learners to recognize meaningful connections between words. Referring to the example mentioned above, kitāb (book), maktaba (library), kātib (writer) maktūb (what is written) all derive from the root k–t–b, which conveys the general sense of “writing.” The precise meaning of each word depends on the pattern applied to the root.

Understanding this system does not just expand vocabulary; it can truly transform how learners think about the language itself and approach various phases of the language learning journey, as the three examples below show.

Roots as pathways to networks of meaning

Familiar (2008), investigated how non-native learners of Arabic infer the meanings of unfamiliar nominals while reading, offering valuable insights into the role of morphology in vocabulary acquisition. This exploratory qualitative study, which employed think-aloud protocols with 11 high-novice and low-intermediate learners enrolled in the Arabic Language Intensive (ALIN) program at the American University in Cairo, found that participants relied on roots in 87.5% of cases, often linking new words to familiar ones sharing the same previously known root.

This finding invites reflections on how morphological instruction can empower learners to build vocabulary autonomously. As Shahbari-Kassem et al. (2024) explain, the process of decomposing a polymorphemic word by extracting its root and deriving meaning through semantic reasoning enhances learners’ ability to expand their vocabulary independently. Training students to recognize roots and patterns and to connect words into networks of related meanings can therefore be a powerful strategy to sustain long-term autonomous vocabulary growth.

Moreover, the study’s results underscore the value of emphasizing depth over breadth in Arabic vocabulary instruction: rather than teaching a large number of isolated words, focusing on fewer words more deeply through their root connections and core meanings can foster more effective and lasting learning.

Emotional engagement: When structure meets meaning through inspirational content

Yet learning is never purely cognitive. As recent research shows, emotional engagement can make or break vocabulary retention.

Habib et al. (2025) studied the use of inspirational Arabic quotes in vocabulary instruction among secondary-level learners in Indonesia. Over three weeks, participants showed improved retention, morphological awareness, and contextual understanding.

This approach highlights the connection between emotional engagement and cognitive processing and underscores the importance of carefully selecting the material and resources in Arabic classes. When vocabulary instruction integrates meaning, emotion and reflection on linguistic form, it stimulates both hemispheres of learning, analytical and affective.

Meaningful, motivational and culturally-grounded materials like Arabic proverbs or short sayings (amthāl) allow learners to notice roots and patterns while engaging with cultural and emotional content. This kind of material supports what might be called holistic vocabulary learning: a process that integrates morphology, semantics and emotional investment into a coherent and memorable experience.

The power of tools: Connections for linguistic and personal growth

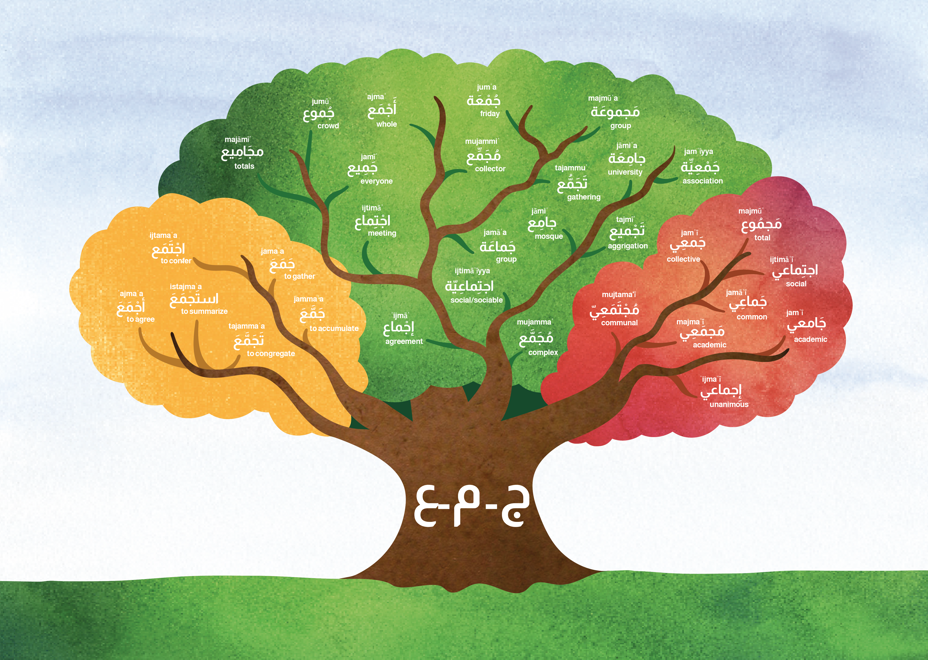

During one of my Arabic classes in Cairo, an adult beginner experienced an “a-ha moment” while using the QFI Arabic Root Tree infographic.1

While exploring the triliteral root j–m–ʿ (ج–م–ع), she suddenly connected yawm al-jumʿa (Friday) to the idea of a day of gathering, connecting the word to the verb jamaʿa meaning “to gather.” Since then, she has shown growing curiosity about morphological and semantic links, asking about connections between words heard in everyday life contexts like maṭbakh (kitchen) and yaṭbukh (to cook).

This example reveals the importance of selecting effective tools for vocabulary building. As Habib et al. (2025) suggest, innovative tools that move away from mechanical memorization and decontextualized word lists should be prioritized into Arabic classes to enhance both depth of comprehension and motivation in vocabulary acquisition.

From this example, it becomes evident the beneficial effects of introducing morphological instruction from the very beginning. As Hassanein (2025) emphasized in the Advanced Arabic Grammar course within the TAFL Master at AUC, early exposure to the logic of word formation represents a cornerstone of Arabic instruction. It helps learners understand the system of the language from the start, providing a framework they will carry on with them throughout all phases of their learning journey.

Indeed, the more Arabic learners advance in their studies, the more words, patterns and concepts they encounter, expanding the spectrum of possibilities for connections and deep reflection grounded in morphological awareness.

In my own experience, morphological reflection continues to be a major source of appreciation for the language across multiple contexts. For instance, it can open new dimensions in understanding literature. When reading the passage from Ahdaf Soueif’s The Map of Love (2012) — “So at the heart of things is the germ of their overthrow; the closer you are to the heart, the closer to the reversal” (p. 46) — I was struck by the interplay of meanings between words sharing a common root in Arabic: qalb (heart) and inqilāb (overthrow). This connection reveals a profound link between seemingly distant concepts, opening the way for a deeper cultural and philosophical way of seeing the world, where form, meaning and emotions are in continuous dialogue.

Remembering to reconnect with this linguistic and cultural depth throughout the language-learning journey is crucial for sustaining motivation and curiosity in the everyday life of an Arabic learner. Projects such as The Arabic Pages beautifully exemplify this, offering reflections that unveil the layers of meaning embedded in everyday common words.

For instance, the blog article “Exploring Time in the Arabic Dictionary: ‘Hour’”2 reflects on how the word ساعة (sa‘a), usually associated with “hour” or “clock,” also carries the idea of “abandonment” through its root س-و-ع, shared with words meaning “to leave someone or something neglected.” This invites new perspectives on time, connecting it with notions such as “loss” which offers nuanced reflections on meaning previously unexplored.

In this way, morphological exploration turns from a mere strategy for vocabulary building into a springboard for an inspiring process of intellectual and personal growth, where words come alive, revealing the endless possibilities of ideas, emotions, and perspectives they hold within them.

Experiencing Arabic flexible and athletic system

“The Arabic language is a very flexible and athletic language ... and its possibilities are as many as the Arabs are many,” Edward Said once affirmed in an interview reflecting on Arab identity and language (as cited in Poetic.com, 2015).

As this post has explored, understanding how word structure relates to meaning in Arabic allows learners to experience that very flexibility and richness embedded in the language. It opens the door to the countless possibilities within its words, fostering a more effective, sustained and intimate learning journey with the Arabic vocabulary and the broader language system.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Qatar Foundation International (QFI). While QFI reviews guest contributions for clarity and to ensure the content is valuable for our audience, the accuracy and completeness of the information are the responsibility of the author.

Submit Your Own Blog!

We invite educators, researchers, and professionals in Arabic education to share their insights with our global community. Whether you teach, conduct research, or support Arabic language learning, your voice can spark innovation, drive change, and deepen understanding in the field of Arabic education.

With a background in journalism, I have written extensively on languages, cultures and societies in the Mediterranean for platforms such as Dialoghi Mediterranei, Egyptian Streets, The New Arab, and Beirut Today, authored Sorprendersi in Egitto, a book reflecting on my linguistic and cultural journey in Egypt and founded the social media educational page @almuhit_theocean, a project that connects Arabic language learning with everyday life in the region. In parallel with my writing, I have consistently pursued Arabic studies, completing the CASA@AUC program in 2023–2024 and earning the TAFL diploma at the TAFL Center in 2021, Alexandria University. I am currently a graduate fellow in the TAFL MA program at the American University in Cairo and have served as a credit curriculum facilitator and teacher at Al-Wāḥa Arabic camp at Concordia Language Villages in Minnesota this summer.

References

Bakker, B. (2020). Learning Arabic vocabulary: The effectiveness of teaching vocabulary and vocabulary learning strategies. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 20(10), 190–202.

Bowers, P. N., & Kirby, J. R. (2010). Effects of morphological instruction on vocabulary acquisition. Reading and Writing, 23, 515–537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-009-9172-z

Elkheir Elgobshawi, A. (2024). Conceptualization of morphological roots in Arabic and English: A contrastive analysis. World Journal of English Language, 14(5), 436–446. https://doi.org/10.5430/wjel.v14n5p436

Familiar, L. (2008). The role of the Arabic root in guessing the meaning of unfamiliar nominals [Thesis, The American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/retro_etds/2233

Fromkin, V., Rodman, R., & Hyams, N. (2003). An introduction to language (7th ed.). Thomson Wadsworth.

Habib, M. T., Masnun, M., Mahmudah, M., & Abdus Syakur, S. (2025). A psycholinguistic approach to enhancing Arabic vocabulary and morphology mastery through inspirational quotes. An Nabighoh, 27(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.32332/an-nabighoh.v27i1.1-24

Hassanein, A. (2025, Fall). Advanced Arabic grammar [Course]. The American University in Cairo.

Poetic.com. (2015, October 1). Edward Said conversation with Bill Moyers: The Arab world, part 1 – The Arabs: Who they are, who they are not [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eI6mjFL80xE

QFI Arabic Root Tree. (n.d.). Qatar Foundation International. https://www.qfi.org/resources/infographics/the-arabic-language-root-system/

Shahbari-Kassem, A., Schiff, R., & Saiegh-Haddad, E. (2024). Development of morphological awareness in Arabic: The role of morphological system and morphological distance. Reading and Writing, 38, 2235–2267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10581-0

Soueif, A. (2012). The map of love. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Thearabicpages. (2025, April 22). Exploring Time in the Arabic Dictionary: “Hour.” The Arabic Pages. https://thearabicpages.com/2025/04/22/exploring-time-in-the-arabic-dictionary-hour/